By her own definition, Lorelle Chapman is a rather “unorthodox and outspoken” chaplain.

During the three years she spent working with Australia’s third-largest iron-ore mining company, her best relationships were made over a beer at the wet mess.

A few years later, after being deployed into the middle of New South Wales’ worst bushfire season, she was awarded with the state premier’s emergency citation for her service.

No, Lorelle is no “banner-waving, street corner preacher”. She is the Hauraki Plains Co-operating Parish’s new resident minister, and she has an open-door policy.

“It’s the people who can’t afford to put bread and milk on the table. It’s the bottles I see in the gutter, smashed to bits. It’s the people I saw lurking in the shadows down by the takeaways who didn’t have anywhere to go. It’s the person who was moved on from sleeping in his car because he couldn’t afford a motel. It’s the domestic violence, the mental health… it’s all of that stuff.

“So, how does the community see the role of the church?”

Lorelle, originally from Auckland, was living in Ohakune when she encountered “inexplicable and interesting” circumstances that lead to her becoming a registered baptist minister.

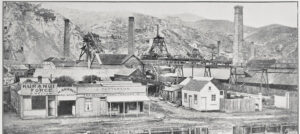

In 2013, she was called into Western Australia to work as a chaplain for a multi-million dollar mining company in the Pilbara desert outback.

Her role was to provide support and spiritual well-being for the 2000 personnel, in what could be a stressful and dispiriting environment.

“It is really isolating, and it was the most challenging time professionally and personally in my ministry life to date, and I was incredibly homesick, and I spent a lot of time on my days off flying back to New Zealand,” she told The Profile.

Lorelle kept up that routine for nearly three years, and said although the role did have its “use-by date”, she did miss it, to some extent.

“You’re in 48 degree heat, and you’re sweating, and you’re living in a donga, you’re filthy and isolated, and you’d all go up to the wet mess and were given a daily allocation of mid-strength beers,” she recalled.

“Some of my best conversations and connections and relationships were formed over a beer at the wet mess… and there were tonnes of things you’d rather not have seen or experienced.”

“I used to say nothing would surprise me, but boy, I was constantly surprised.”

In 2016, Lorelle joined the “incredibly progressive” Uniting Church in Australia, and was working as a hospital chaplain before becoming involved in the church’s Disaster Recovery Chaplaincy Network.

As a specialist arm of chaplaincy, Lorelle’s job was to “hold up” the people affected by a traumatic event, as well as those working on the frontline.

She was back living in New Zealand when she was sent to Kempsey during New South Wales’ ‘Black Summer’ – the state’s worst recorded bushfire season that occurred across 2019–2020.

Over the course of a few months, 26 lives were lost, 2448 homes were destroyed and 5.5 million hectares of land was burnt.

“What hit me was just the difficulty I had breathing,” Lorelle said. “The air was so thick.”

She received a Bushfire Emergency Citation, an award issued by the Premier of New South Wales, for her emergency service during the bushfire season.

“I did nothing. I got a citation for talking to people and having cups of tea and drying their eyes,” she said. “It was the firies, and the ambos… they’re the heroes.”

Lorelle said her work with the network was a very “humbling experience”, but something was beckoning her home.

She returned to New Zealand in March and was appointed by the Presbyterian Church of NZ to be the Hauraki Plains Co-operating Parish’s new resident minister.

In her first few weeks, she arranged a free community sausage sizzle at the front of the church “just because we could”, and her goals continue to expand outside the church doors.

“Slow and steady wins the race,” she said. “I’m just interested in people… and I think there’s something really special and significant about the Plains.”