As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley

After William Guy buried his brother at Thames in October, 1923, he returned to his home in Ngātea.

William, 47, had been employed by the Lands Department for many years, working all over the Hauraki Plains. But now he handed in his notice, drew his wages and paid up his account at the store. He told his friends he was leaving. William talked of the great suffering that his brother, James, had endured. James, 50, had had the dreaded miners’ phthisis, or miner’s complaint – a lung disease caused by inhaling crystalline silica dust. Now William, who had also at one time worked as a miner, had it too.

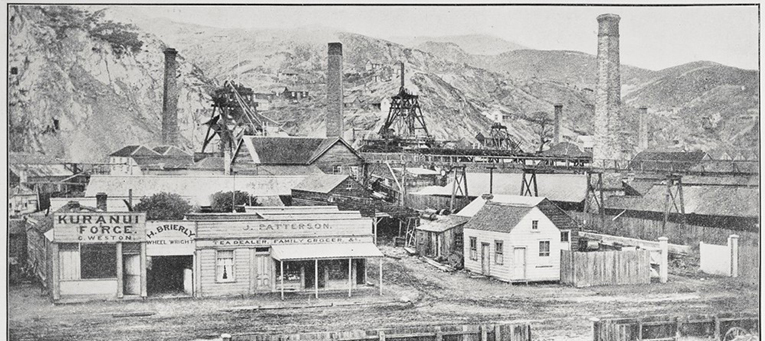

Twelve years earlier an investigation into miner’s complaint had been held at Thames. Dr Lapraik said that impure air, faulty ventilation, absence of sunshine, temperature changes, dampness, poisonous gases, decomposing timber and insanitary surroundings contributed to miner’s phthisis.

The remedies were good ventilation, cleanliness, and the use of water spray wherever quartz was being broken. He advised a hot bath, followed by a cold shower immediately on coming to the surface. Dr Walshe said that chronic lung disease amongst miners was very prevalent in the Thames district and miners should be prevented from spitting indiscriminately about a mine.

In 1915 at a parliamentary discussion, the compensation for cases in which miners died of miner’s complaint was declared utterly inadequate. It was considered an absolute scandal that nothing had been done after the matter had been discussed for so many years. The government was urged to provide invalid pensions.

Dr Thacker pleaded that in addition to the soldiers at the front, these “industrial soldiers” should also be looked after.

After William Guy had said goodbye to his friends, he was found a few hours later lying on the bed in his hut, having taken his own life. At the inquest, a verdict of suicide while in a depressed state of mind was returned. William was a single man, well and favourably known throughout the district. Suicides by men suffering from miner’s complaint were quite frequent; it was a grim and frightening disease.

The year after William died, a Bill was passed that miner’s incapacitated by miner’s phthisis be entitled to a pension, together with the necessary medical comforts and medicines.

The Bill was supported by Mr Rhodes, member for Thames, who said it had been most unreasonable that a man was not allowed to receive the miner’s pension if he were able to do any work at all. Many of the men could do light work, but the average miner, who had been mining all his life, was a miner, pure and simple, and how could he be expected to do anything else? Thames men who were almost at their last gasp had been having to make a journey to and from Morrinsville to prove whether they had the disease or not. If he was suffering from miner’s complaint, a man had quite enough to do in finding the next breath.

William died just 10 days after James. They are both buried at Shortland cemetery, Thames.