As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES searches through old newspapers to bring you the stories Thames Valley locals once read about themselves.

1868

A curious mineral water discovered at Puriri was analysed, and from its nauseous effect on the palate and action on the bowels it was dismissed as nothing more than a laxative. Mining at Puriri though, showed more promise.

A foundation for a twelve stamper battery and a waterwheel were in place and it would not be long before Puriri night owls were disturbed by the click-clack of iron stampers spinning round doing their fifty-five per minute.

A man named William Pennell left Thames in an open boat to cross to the Miranda Redoubt. When about six miles out a wave struck the boat and before she could recover was overtaken by a second one, which filled and sank her. She had on board flour, salt and other assorted goods.

The boat and cargo were lost but the man was picked up by a passing fishing boat and landed safely at Grahamstown.

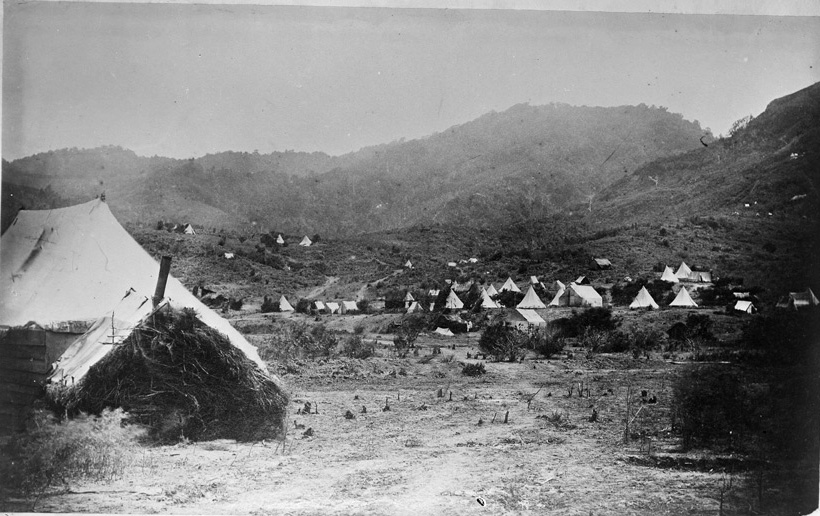

The township of Hastings (Tapu) boasted six public houses, six share brokers’ offices and one butcher. About 2000 diggers were scattered around this part of the country, and every gully and spur was taken up by miners. From a distance, the numerous drives made into nearly perpendicular cliffs looked like pigeonholes and the rugged ranges were dotted with small white tents.

If one followed the gorge for miles, climbed over waterfalls and scrambled up various spurs where a goat could scarcely find footing, there was the digger, his tent and axe.

Thames, the “Land of Gold” was denounced by a scornful visitor. There was lots of mud, plenty of rain, heaps of loafers and hard up people, but very little gold.

He pronounced the place a gigantic swindle. Gold was there but to get it out you needed gold in your pockets; it was useless a man going to Thames, unless he was prepared to keep himself in tools, clothes and provisions for twelve months at least. Many of the claims were four or five miles back in the ranges; the men had to hump their provisions up, and their quartz down, as the hills were too steep to get up with a horse.

The whole yield of gold for twelve months past did not average more than three ounces per man.

The only way to work it profitably was by forming large companies with plenty of money. There were thousands of people who would gladly leave and there was talk of the government chartering a vessel to take them away, but the worst of it was that every vessel that arrived brought more and more men.

How the deuce they were going to live the vexed visitor did not know.