As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley.

No one could convince Father James Norris of Thames to slow down during Easter week in April, 1874.

The 35-year-old had imposed a severe discipline on himself in observing the Catholic traditions of Easter – praying, delivering sermons, and fasting during Lent. By Easter Sunday, Father Norris was noticeably ill and his immediate friends became alarmed, particularly as it appeared the strain on his physical capabilities had affected him mentally.

“We regret to learn,” reported the Thames Advertiser, “that the Rev Father Norris is suffering from a severe indisposition of a nervous character. We hope the rev gentleman will soon recover from this illness, which has in a great measure been brought on by over-exertion during the past week.” His parishioners were greatly concerned. Father Norris had succeeded Father Nivard as Thames’ Catholic minister just 10 months earlier. He was an eloquent preacher and quickly established himself in the affections of his flock. He was respected by all denominations at Thames for his religious dedication and his quiet, unassuming demeanour as a citizen.

James Norris had been born at Piltown, Kilkenny, Ireland, and studied at Carlow College before coming to New Zealand. He was ordained to the priesthood in Auckland in the mid-1860s and was for some time in charge of a large district on the East Coast, residing at Ōpōtiki, where he was universally liked. He was then removed to the South and it was mainly owing to his energy and zeal that the Ōamaru church was freed from debt. When returned to Auckland Province, he was pastor in St Patrick’s Cathedral.

Now Father Norris was obviously suffering from a serious mental aberration and he was taken by the Rev Father Golden and other friends to Auckland where he was admitted to the Whau Asylum. It was hoped that the change of air and scenery would restore him to his usual health, but Father Norris remained in a disturbed condition for nearly three weeks. Suddenly he came out of his strange state and became quite alert. He was aware that his recovery of reason showed that he was near death and he calmly prepared for the coming change. He had several interviews with priests, speaking placidly of his demise, and mentioning his parents and friends in Ireland. The next morning, Mrs Robertson, the wife of one of the warders at the Asylum, asked that he be removed to her house, just outside the Asylum gates.

Dr Aicken consented and Father Norris was taken there late morning. He died around 2:30pm and was laid out at St Patrick’s Cathedral soon after midnight.

At Thames, his loss was keenly felt and there was intense regret amongst all classes of the community.

When the news reached the South he was remembered as a gentleman in the prime of life, with a kindly and genial nature who made friends of all he came in contact with. Father Norris was a man of the highest standing, and of powerful, as well as cultivated, mind. He was a scholar, a gentleman, and a Christian whom the Colony could ill afford to spare. The loss to the Church and the ministry to which he was so devoted was considered irreparable.

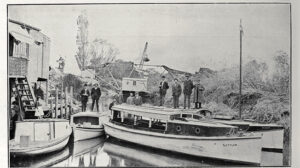

The day before his funeral the Thames branch of the Hibernian Society, of which Father Norris was chaplain, as well as a large number of the members of the congregation and other Thames citizens proceeded to Auckland by the Golden Crown steamer. Many others who were unable to get away by the Golden Crown left at night by the steamer Enterprise.

Father Norris’ funeral was the largest ever witnessed in Auckland. It was also one of the most imposing ceremonies – the full and splendid ritual of the Romish Church being employed on the occasion. After Requiem masses, the Hibernian Societies of Thames and Auckland, having been invested with the regalia of their orders, walked in procession to the Cathedral. At 3pm, the funeral service of the Roman Catholic Church was performed by the Vicar-General who gave a very impressive address in which he referred in affectionate terms to the career of Father Norris. The church was crowded to excess, a large number being unable to gain admittance. Among those present were nearly 200 mourners from Thames representing nearly every corporate body, political, religious, and social, at the goldfields.

Around 5000 people marshalled for the funeral procession which included the Processional Cross, girls carrying wreaths, girls from St Mary’s Orphanage, boarders from the Convent schools, members of the Catholic Institute, members of the Christian Doctrine Society, the Hibernian societies, Sanctuary boys, the clergy, and several priests. A large number of private mourners in carriages and on foot joined the procession as it passed along. Houses were arrayed with black fabric mourning drapes and men in the street raised their hats every yard of the way. When it arrived at the church, the procession had swollen to an enormous length. Father Fynes completed the service at the church and grave.

The next morning, representatives from Thames were hospitably entertained at the Presbytery in Wyndham St before their departure on the Golden Crown.

The resident Fathers thanked the visitors for the solicitude for their pastor’s fate. There were many reflections on the untimely death of Father Norris, who it was felt was taken in the inscrutable wisdom of the Almighty in the summer of his life and usefulness.

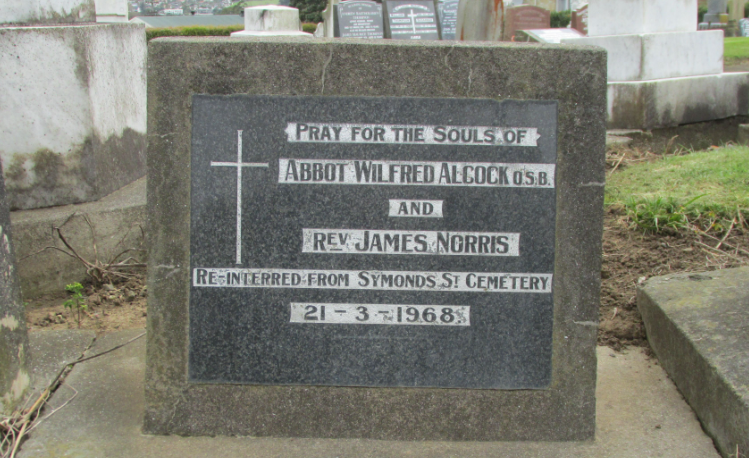

Father Norris was buried Symonds Street cemetery Auckland, but re-interred 94 years later with Abbott Wilfred Allcock at St Patricks Roman Catholic cemetery, in 1968.