John Duncan, straddling the wild pig he’d just killed, lit his pipe with satisfaction.

It had been a good Sunday morning in April, 1874, hunting with his wife Riripeti (Elizabeth) at Opani Point on the swampy land opposite the mouth of the Waihōu River. John told Elizabeth they would carry the pig to where the other ones they’d caught were.

He drew the gun, which was lying on the ground in front of him, by the muzzle to give to her. Suddenly the gun exploded, a bullet entering the left side of John’s chest.

Elizabeth rushed to him and he lay his head in her lap. The last word he spoke was her name.

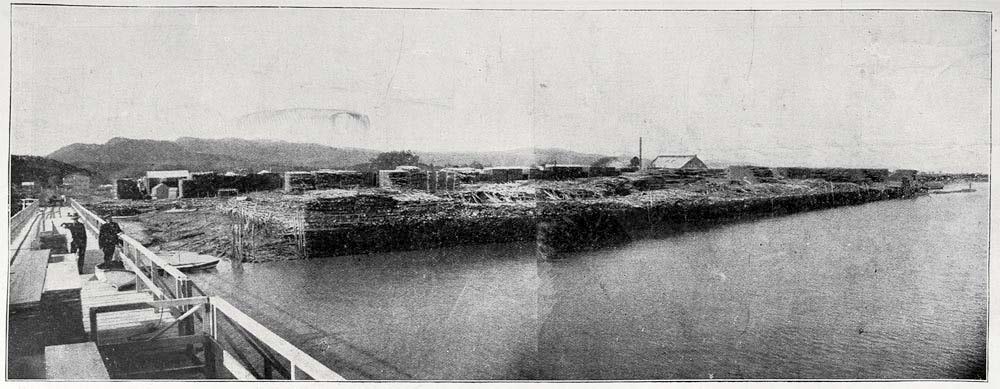

Distraught, Elizabeth went to the bank of the river opposite Mr Gibbons’ new mill at Kōpū. She called to the people she could see there but they didn’t hear her. She then attempted to swim across the Waihōu.

Looking back she saw a canoe lying in a creek. She swam back to the shore, and dragged the canoe into the water, subsequently reaching the other side.

She asked the Kirikiri Māori to go back with her to where she’d left John, about a mile from the river, in a swamp, but they were afraid to.

Elizabeth, exhausted and shocked, then walked to Shortland, arriving in the dark, and informed the police.

As it was too late to do anything, it was arranged to send over a boat at daylight.

Constable Madill and a boats crew, after great difficulty, found John’s body the next morning. At the inquest, held in Shortland’s police courtroom, the Coroner said that if the jury were satisfied with Elizabeth’s evidence, that death resulted from a gunshot wound, it would be unnecessary to call any medical evidence.

Elizabeth told the court that she and John had always lived together on good terms except when either of them had taken liquor, but he had not been drinking lately, and they had had no quarrel.

She had saved his life from drowning once. Her deposition was read back to her, which she signed with her cross. Constable Madill described the difficulties of the search and how John’s two dogs were by his body and couldn’t be persuaded to leave it. The jury returned a verdict of accidental death.

John Duncan was well known in Shortland.

A Māori language interpreter, he had extensive dealings with local iwi. He and Elizabeth had married in Northland in 1863, possibly arriving in Thames with the 1867 opening of the goldfield.

John was a Roman Catholic but the priest refused to have anything to do with the funeral. Father O’Mahoney had asked Elizabeth when it was on Sunday morning that they went over to Opani Point to shoot pigs. Elizabeth replied that it was early. Father O’Mahoney then asked if John had been at mass that morning and on being answered no, he replied that he could have nothing to do with the burial. Local Māori had no such qualms and John was buried in a small piece of tapu ground at the back of the Shortland sawmill on the corner of Grey and Pollen Streets.

Gibbon’s sawmill, Kōpū, on the Waihōu River. From an opposite bank Elizabeth’s desperate calls for help

went unheard. Photo: SUPPLIED