As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley.

Charles Pell was found lying on the floor of his tent on a Friday morning in December 1911. Unable to revive him, his work mates phoned the Thames police. Charles, 42, who usually lived in Thames with his wife and family, had been working on a drainage contract at Duck Creek, Turua and it was there that Sergeant Crean despatched Dr Lapraik and Constable Neal.

Charles had attempted to poison himself by taking a dose of Lysol, an antiseptic disinfectant. Dr Lapraik phoned Thames hospital with the message that the case was a most critical one and that there were grave doubts that the man would recover. Charles was brought to the hospital unconscious but then began to rally. The next he deteriorated, dying at 10.15 that night.

It had been observed by his workmates that Charles worried a good deal and had been somewhat down but his wife, Lucy, had no idea why he would take his life. Sergeant Crean though had taken a statement from him at the hospital in which Charles said he was tired of living under his present conditions.

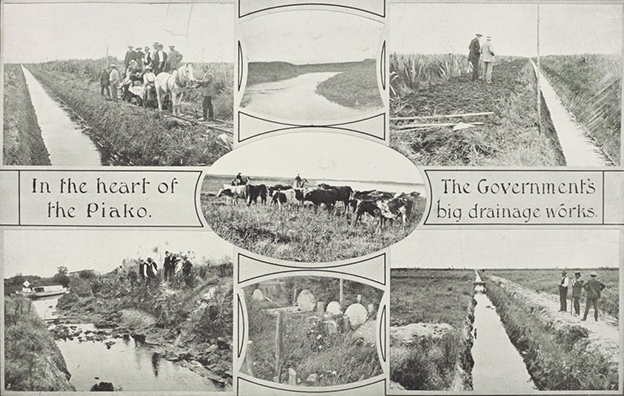

Charles was part of the labour force working on the massive drainage operations on the Hauraki Plains. By 1911 the land drained amounted to 6800 acres. The works completed include 27 miles of stop banks, 35 flood gates, 19 miles of cart roads, seven wharves, 30 small bridges, 14 miles of private telephone line, and nine artesian bores. An average of nearly 300 men was employed and there were 187 separate contracts in progress.

Working conditions for these men were wretched. Tents were frequently flooded out and despite manuka wind breaks they shook alarmingly in the wind. Drain diggers had to work in water, while the surveyors splashed around bare-legged in the marshy ground. Men stood up to their knees in cold swamp water, throwing out the sodden squares of peat or clay. They are wet all the time. They couldn’t dry anything and each morning pulled on soaked and muddy pants and boots. Communication between the outside world and the workmen’s camps was unreliable. The only connection with the nearest town was by launch to Thames. Life was harsh for this great body of physical workers and for Charles Pell it became all too much.

At the inquest it was found that Charles had a horse with a bad shoulder which he treated with Lysol. Dr Walsh said that Charles had died from shock from enteritis, due to taking a dose of Lysol. Both he and Dr Lapriak deplored the indiscriminate and unrestricted sale of such a deadly poison. A verdict of suicide from Lysol poisoning was returned, with a recommendation that it should be sold with legal restrictions. Lysol was stocked by grocers and others as a general disinfectant.

It had originally been introduced to help end a chorea epidemic in Germany, but instead of saving lives the misuse of this irritant poison caused many excruciating deaths.

Charles Pell is buried at Shortland cemetery, Thames.