As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley.

As you see I am still hanging on,” wrote 28-year-old George Millar to his Paeroa parents from Turkey in 1915 in the thick of World War I’s Gallipoli campaign.

His other piece of good news was that “I received postcards and letters from home this week”.

Letters in war time were vital to morale, keeping men and women connected to the homes they had left behind, and those at home linked with their loved ones.

During the early days of war, the sons of Thames Valley residents were in training in Egypt and their letters were received fairly regularly.

There was little anxiety about their sons’ safety, but then the scene changed – since active service had begun letters were irregular, and opened with fear and trembling.

On 25 April, 1915, New Zealand and Australian soldiers landed at what is now called Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula. For most of the 16,000 men who landed that day, it was their first experience of combat.

By that evening, 2000 of them had been killed or wounded.

The Ohinemuri Gazette gravely observed: “Until now the real horrors of war with all its cruelties and sorrowing consequences, have not broken upon us with such reality. Until the Dardanelles [Gallipoli] engagement, where some of the brave boys of our town are in action, we could only conceive in a vague way the awful realities of the situation”.

“We knew of course that thousands of innocent lives were being sacrificed every day . . . but it did not come home to us as it does now.”

George’s experience he summed up almost jauntily – “We had another big battle on the 19th inst, and lost a number of men including two of our signallers”.

“The Turks suffered very heavily; in a short section of trench where I was fighting, we polished off between two and three hundred. The attack was so severe that they got right up to our parapets before we stopped them.

“In a few cases the enemy rushed into our trenches, but we immediately bayoneted… Our next bit of excitement was on the 25th, when one of the enemy’s submarines torpedoed and sank the battle ship Triumph… It is bad luck losing a ship, which since we landed has given us a great deal of assistance.

“Since the last incident, things have been fairly quiet. Today we have had only an occasional shell to keep us alive.” He ended his missive home with – “Goodness knows how long this war is going to last. It may end any day. Let us hope that it will soon be over and I can get back again. I have seen enough of war to do me a lifetime . . . Don’t worry one bit about me; I am in the best of health and so far have been lucky enough to dodge ‘Turkish Delight’.”

But worry stalked those left behind and post offices and postmen were sought after every day for news of absent ones while newspapers contained horrifying lists of those killed or wounded.

The young men of the district were impressive in their willingness to be always so ready to go to the front and fight with all their heart and strength for country, King, and liberty, yet hearts were heavy as more and more youths from the surrounding district volunteered for service.

In July, 1917, a large group of people gathered at the Paeroa railway station to see the arrival and departure of the express train from Thames, which carried still another contingent to Frankton Junction, en route for Awapuni military camp, near Palmerston North, to prepare for active service abroad.

Some of the young men embarked from Thames, while others stepped on at different stations along the line. As the train drew up the scene became more emotional, and mothers, sisters and sweethearts pushed forward with tears and affectionate goodbyes.

The new soldiers were not in khaki, but when they arrived at camp their uniforms would be immediately dealt out to them, together with other items of clothing and bedding.The young soldiers, after a life of two or three months in camp would return again to their homes. They then had final leave for ten days, after which they would be considered fit for active service. At any time after the end of their leave they would be called on to prepare for life on the ocean and an uncertain future.

One of these boys was Archie Lyes, 27, from Waikino, whose initial experiences were published in the Gazette near the end of 1917 when there had been a surprise meeting in London of three Paeroa soldiers. Archie, of the Medical Corps, on three days’ leave wanted to see the “lights of London”.

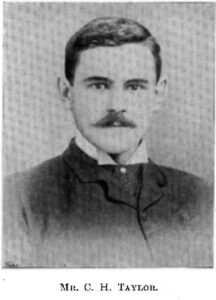

He had only been there one day when he came face to face with Victor Taylor, son of a Paeroa Councillor, and Ted Nelson, who was employed building the Public Works dredge in Paeroa. It was a happy recognition, and “a merry time was spent, but the time came when the best of friends must part: the bugle called, and the three Paeroa chums were off to the war again”.

Within a few short weeks the tone of Archie’s letters had changed and the next described the “Horror of the Trenches”.

Writing from a military hospital after being gassed, he said: “When one is in France in active service, one has to endure many hardships… he has to traverse many miles of rough country, quite uncommon to that of the lands of New Zealand. This we had to do after a close confinement in the trenches for ten days, with hard fighting all the time. We went through the period – which seemed to us all a year or more – with but little sleep and without a wash to refresh ourselves. During the term in the trenches, our rations were extremely short.”

At the military hospital, he was in the same ward as a couple of other New Zealanders. The nurses were all Australians, and extremely kind to the sick and wounded. Archie also had a British a roommate – a very fine specimen of a man, about 45 who had a family of three, who despite his age had been called up to do service. “I saw some letters from his children, which would make the most hardened shed a tear.

“Whilst the father was in the midst of battle on one side, his wife and children on the other side were forever dodging air raids.” Archie wistfully added: “I am still on the sunny plains of France, but things in the true sense are not as sunny as they are in dear old Paeroa”.

Keeping things sunny was strongly urged by Archdeacon Hawkins, a returned New Zealand chaplain. “All the lads’ letters from the Front are bright… some people seem to think that soldiers merely affect a brightness for the benefit of their friends and wives but this is not so. Their words truly reflect their spirit… Whatever pessimists there are, they are not at the Front. I certainly ought to know, because I have censored thousands of letters.”

It was important that letters from home should be equally bright. “There should be no worrying details of anything sent to the soldier. He cannot help. The letter reaches him months after the details have been set down, and just when the letter makes him worry, the writer may have experienced a beneficial change that made the letter quite unnecessary.

“Keep your letters to soldiers entirely bright!” is the slogan for those who are writing to soldiers, “and when they come back don’t pester them with war talk. They don’t want it”.