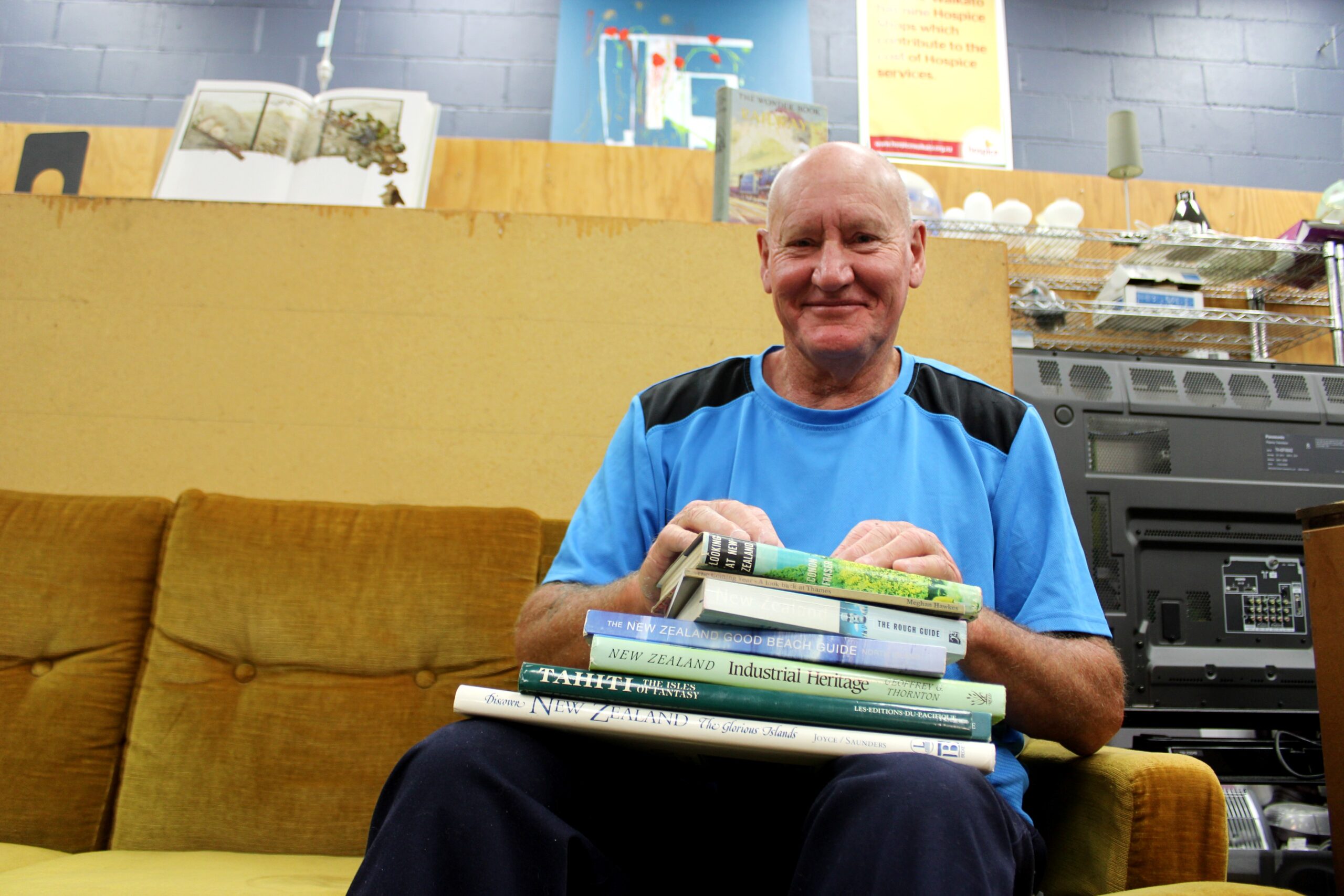

Stephen Ranger has amassed thousands of books about his favourite subject – New Zealand history.

He enjoys the ones about Maori culture, kauri trees, flax, and gold mining, but there’s one question he always gets asked when someone stumbles upon his collection: “How come you have so many books when you can’t read?”

For 65 years, Stephen hasn’t been able to read and write, and for most of his adult life, he used the maunga [mountains] of Auckland to navigate.

But now he’s given himself a goal: to learn literacy with the help of Te Korowai.

“I could’ve said to myself ‘I’m not going to bother’, but I want to leave the world knowing how to read,” he told The Profile.

Stephen was born prematurely in Mt Roskill, Auckland, in 1958. From the start, he said he struggled with reading and writing and was placed in a special learning class in primary school.

He only spent about two years at high school and got the cane and the strap “quite a lot”.

He said he didn’t understand the words on the board or what they meant, and often felt like a “square peg in a round hole”.

But he was good at other things: swimming, woodwork, and technical drawing, and after being expelled from school at 14, he went on to work at a furniture removal company sweeping the floors and doing other tasks.

In the 1980s, he started his own cleaning business which became a success.

“I stayed away from that world of reading and I did that for years and years and years,” he said. “I cleaned pubs and hotels and nightclubs and the windows of highrises, and whenever anyone asked me how I got around Auckland, I’d tell them how I looked at the mountains. I’ve always been good at memorising things.”

Stephen even passed his drivers licence by remembering the shapes of the signs.

He’s lived in Thames now for 20 years and said he no longer wanted “to just get by”.

“I’m learning to remember my phone numbers off by heart, and how to use a money machine without it gobbling up all the money, and my home address in case I hurt myself,” he said. “I never had to use my brain because I went by my ears – I was listening all the time.”

About three months ago, he approached Te Korowai Hauora o Hauraki for literacy help, and since then, prevocational navigator Romi Curl has helped him from the ground up.

Romi, a former teacher, offers creative opportunities for free within the community, such as journaling and CV writing, as well as the literacy sessions Stephen has taken up.

They meet once a week and Romi, who believed Stephen had dyslexia, said he was making great progress.

“One of the things that I was really impressed by is that he’s always been able to make a living without that [literacy] skill. It is much easier to learn things when you’re younger, but he’s making amazing progress,” she said.

They’ve begun by chronicling Stephen’s own life story, seeing as they both share a love of history.

“I’ve still got a long way to go,” he said, “but I’m running on determination.

“If you put your mind to something and if you want something bad enough, you will do it.”

During the 1980s, Stephen met his future partner Shirley, who was brought up in a family of 13.

She told him how her father would bring all of the children together to teach them how to read and write.

Stephen said he was so thankful for Shirley’s help over the years, but he no longer wanted to rely on her.

“If it wasn’t for my partner beside me being my right hand, I would be lost. She’s there for anything, and she’s been there for 25 years.”

Stephen said if there were any others within the community in similar shoes as his, they didn’t need to feel embarrassed.

“Life can throw you sh*t and give you everything at the same time. You don’t need to be embarrassed about it.

“I don’t care if it takes me the rest of my life to learn how to read,” he said, then with a smile: “But I hope it doesn’t!”

BY KELLEY TANTAU