As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley

PART TWO

Read part one in last week’s Valley Profile

The loss of her husband was a catastrophic blow to Hugh Hill’s wife, compounded by her precarious financial situation. But the community pulled together and in May, 1886, fundraising efforts began for the relief of the families of the two men killed. Mrs Casley stated she had been provided for – her husband, Thomas Casley, had his life insured. She said whatever funds were raised be solely devoted to Mrs Hill.

One hundred subscription lists were printed, a fundraising lecture was given on ‘Billy Brag the Cornish miner’, the Manukau Gold Mining Company donated two guineas, the Waiotahi Company five and the Thames Drainage Board gave 10 pounds, all in aid of the widow Hill. But by August, things had begun going wrong for Mrs Casley who found herself tripped up by a new law. Her husband had no will made and according to the old law, his father could claim one half; the new law only allowed the father one third. Mr Casley successfully put in his claim on the 12th of May for every shilling he could claim.

By early 1887, both Mrs Casley and Mrs Hill had become bitter.

They wrote an astonishing letter to the Thames Star expressing their disgust that the Humane Society was to award bronze medals to the 13 men who tried to save their husbands.

They did “not think it was very brave of the men when they found the body of Thomas Casely to turn the hose on him . . . then to put him in the cage on his head, tie him in it with his feet up and not one of those brave men would come up in the cage with him . . . we are only weak women but if we had known the position our dear husbands were in, we would have rushed to them and have come up in the cage with them.”

The rescuers replied that in No 3 level they found the chamber was partly clear of gas owing to the stream of water coming down the shaft but it was with the greatest difficultly they got the candle lit. Thomas Casley was found first and raised out of the deadly gas by the men who were nearly suffocating themselves. He was placed carefully in the cage in a sitting position, but his boots were hanging out a little, and for fear they would catch on the shaft going up they were tied back to the bar.

“We defy Mesdames Hill and Casley, or any other person to deny that Thomas Casley was not sent to the surface in as comfortable position as was possible under the circumstances . . . we are very much afraid, had Mrs Hill and Mrs Casley been at the No 3 level on that occasion, they would not have been so anxious to rush to their dear husbands as they would have the public believe.” They had the deepest sympathy for the ladies, but they advised them both to stick to facts and write their letters themselves. Whoever the writer was, he was either a rogue or a fool.

“We feel sorry that Mrs Hill and Mrs Casley should so far forget themselves as to put their signatures to such an inhuman scrawl.”

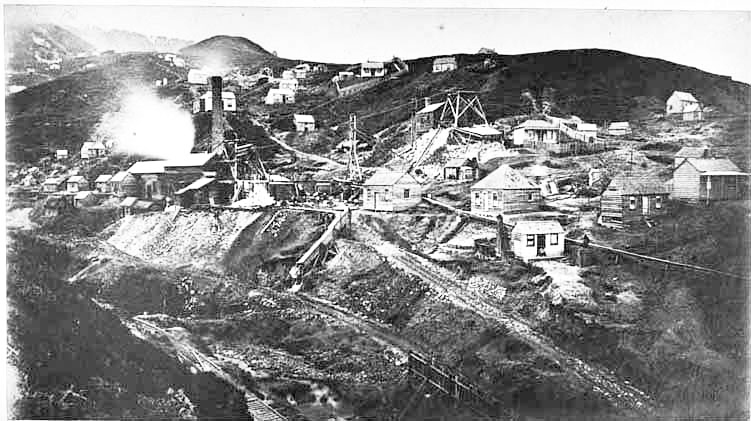

On September 27, 1887, at the Academy of Music, a bronze medal was presented by the Royal Humane Society to 13 men for their efforts to save the lives of Thomas and Hugh when overwhelmed by bad gas in the Caledonian Mine.