Alongside their regular lessons on reading, writing, and maths, the students at St Joseph’s Catholic School in Paeroa are learning to understand themselves.

For the past three years, the school has been fine-tuning a social and emotional literacy teaching framework, dubbed Cognitive Affective Learning (CAL).

It was developed in association with Mary-Anne Murphy from emotional intelligence consultancy RocheMartin, using extensive feedback from the school’s community.

The framework is “quite special”, principal Emalene Cull said, and has garnered interest from the Education Gazette and the New Zealand Principals’ Federation magazine.

“It’s brilliant because it’s confidence building, and it’s honouring and teaching the whole child, not just academically,” she said.

“It’s beautiful seeing our kids showing empathy and being optimistic and resilient, which are the skills and the qualities that are going to set them up for life, not just for when they’re at St. Joseph’s.”

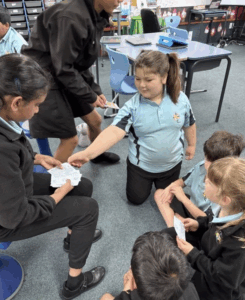

The framework, which is fully integrated into the school’s formal learning processes, focuses on empowering students to recognise and manage their own social and emotional needs.

“Unless we have got the social and emotional wellbeing in check, the process of learning becomes very difficult,” Emalene said.

“Through addressing those social and emotional needs, we can lessen the cognitive load, so therefore the working memory can actually do what it needs to do.”

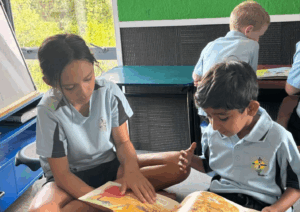

Like most literacy programmes, CAL begins with the basics. Year 0-2 students learn the vocabulary for their emotions, how they feel and look for different people, and explore how feelings are expressed in stories.

For middle-schoolers, the framework introduces neuroscience – the “upstairs and downstairs brain”, and the impact emotions have on learning and relationships – and begins developing strategies for self-regulation.

“For our seniors… They’re heading into their early adolescence, and so the peer relationships change, and they’re starting to look at the world with their own eyes,” Emalene said.

“It’s amazing the things that they talk about in terms of stress and anxiety. It’s big world stuff, and I think part of that is the availability of information to our kids through social media and what have you, and sometimes they don’t know what to do with that.”

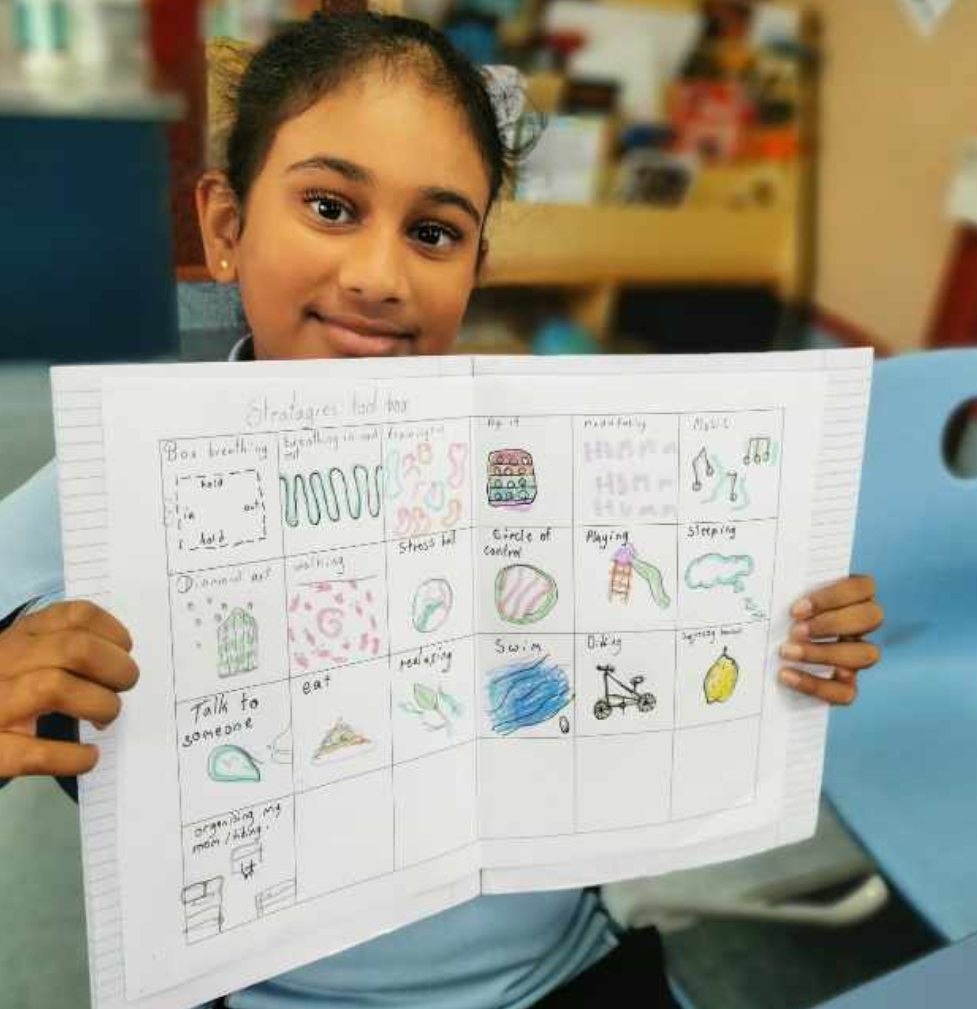

The key with this age group, Emaline said, was developing a “toolbox” of strategies to help students understand what is and isn’t within their control.

“They have opportunities for journaling, but for some kids it doesn’t work.

“We have one kid who [will] say to his teacher, ‘I just need to go for a run’, and he’ll pop out for a couple of minutes and he’ll come back in and be back to [emotionally] even again. So it’s kind of knowing the kids as well.”

The impact the framework has had on St Joseph’s 60 students was substantial, Emalene said.

“We have noticed shifts in our children academically, which we can only put down to that style and flavour of teaching in our school,” she said.

“Our achievement data in reading in 2021 was 65 per cent. And then we started our work with social and emotional learning.”

Reading achievement has climbed steadily since, Emaline said, reaching 88 per cent in 2024. Emalene noted the figure was closer to 95 per cent when adjusted for an influx of English as Second Language learners during the year.

Now, the school is hoping to use this framework to benefit students elsewhere, with a trial at St Joseph’s Catholic School in Te Aroha.

“It’s powerful stuff, powerful learning,” she said.