As part of a Valley Profile series, MEGHAN HAWKES explores our local history by seeking out stories of life and death in the Thames Valley

PART ONE

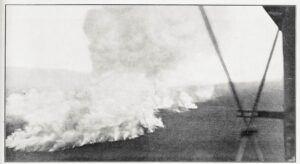

“There is a flax mill being put up at Kōpū… I hope it may succeed and prove a paying enterprise as there is plenty of the raw material in this district, which only wants dressing to be fit for export,” enthused a Daily Southern Cross reporter in 1865.

But things were never quite right at the Kōpū flax mill.

Established two years before gold was officially discovered at Thames, the New Zealand Company’s Kōpū mill was in an area sparsely inhabited by Europeans but home to the Ngāti Maru and Ngāti Tamaterā iwi.

The Europeans called Kōpū “New London” or “Richmond” and the Waihōu River the “River Thames” but the optimistic renaming belied much unrest.

In the end the Kōpū Flax mill left death, whispers of witchcraft and financial ruin in its wake.

The mill began with a capital of eight thousand pounds, five thousand of which was spent on machinery, labour and freight, leaving three thousand pounds to finish the works and build houses for the manager, directors, engineer, and workmen.

By December, 1865, it was almost ready to commence operations although there were difficulties over obtaining fresh water. Negotiations were made with Māori at Kirikiri to allow water to be conveyed from there to Kōpū.

Fresh water was vital to the mill – as part of the process flax was subjected to a constant stream of it.

Strong, active lads were invited to apply for positions and tenders were called for to supply forty tons of green flax to the works weekly.

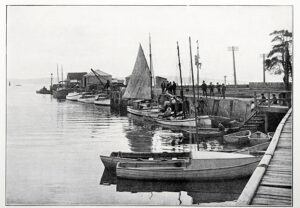

Cutters from Auckland sailed for Thames with flour, potatoes, pork, and workmen for the Kōpū Flax Company.

By January 1, 1866, the mill was up and running but there were disagreements between the New Zealand Flax Company and Māori concerning the price of flax. James Mackay, Civil Commissioner, came from Auckland to handle negotiations. The first cargo of 16 bales of prepared flax from the Kōpū mill arrived at Auckland by the cutter Éclair on February 21 where it was stored for inspection.

In March, ominous news reached Auckland. Paora Te Waitau, an elderly man who lived near the flax cutters camp at Hikutaia, had been killed, cut down by a flax hook by one of the white men employed at the Kōpū mill.

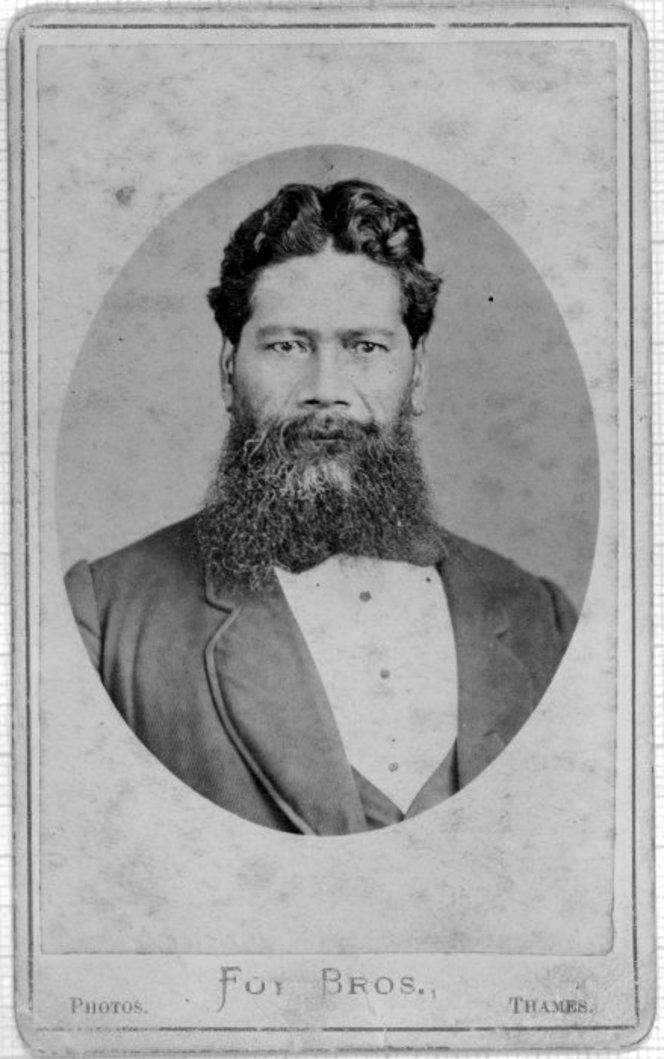

James Mackay lost no time in returning Thames, leaving in a five-oared whaleboat. He took with him Te Hauauru Hotereni Taipari, Māori land assessor of Thames, and five others belonging to the district.

The alleged murder was a disaster. The Thames area, which was being opened to European enterprise, could be closed indefinitely, and the money invested in the flax mill at Kōpū stood a great chance of being lost. Politically, it was regarded as the most important matter that had occurred since the Māori land wars, and a terrible outcome was expected. PART 2 NEXT WEEK